Back to the Office No More

Empty Manhattan office spaces are a real shock to the system. But living and working in a full-time virtual reality has its limitations.

I went back to the office one day last week, for the first time since February of 2020. It was a disconcerting experience.

I was only there for about an hour, for a brief but important meeting with one of my law firm's leaders that was best accomplished face-to-face. Though I "retired" as a Partner in the firm in April of 2022, I have actually stayed on in the position of Senior Counsel to work on some specific ongoing projects. So I've continued to work with some of my colleagues and attend occasional meetings online or via telephone.

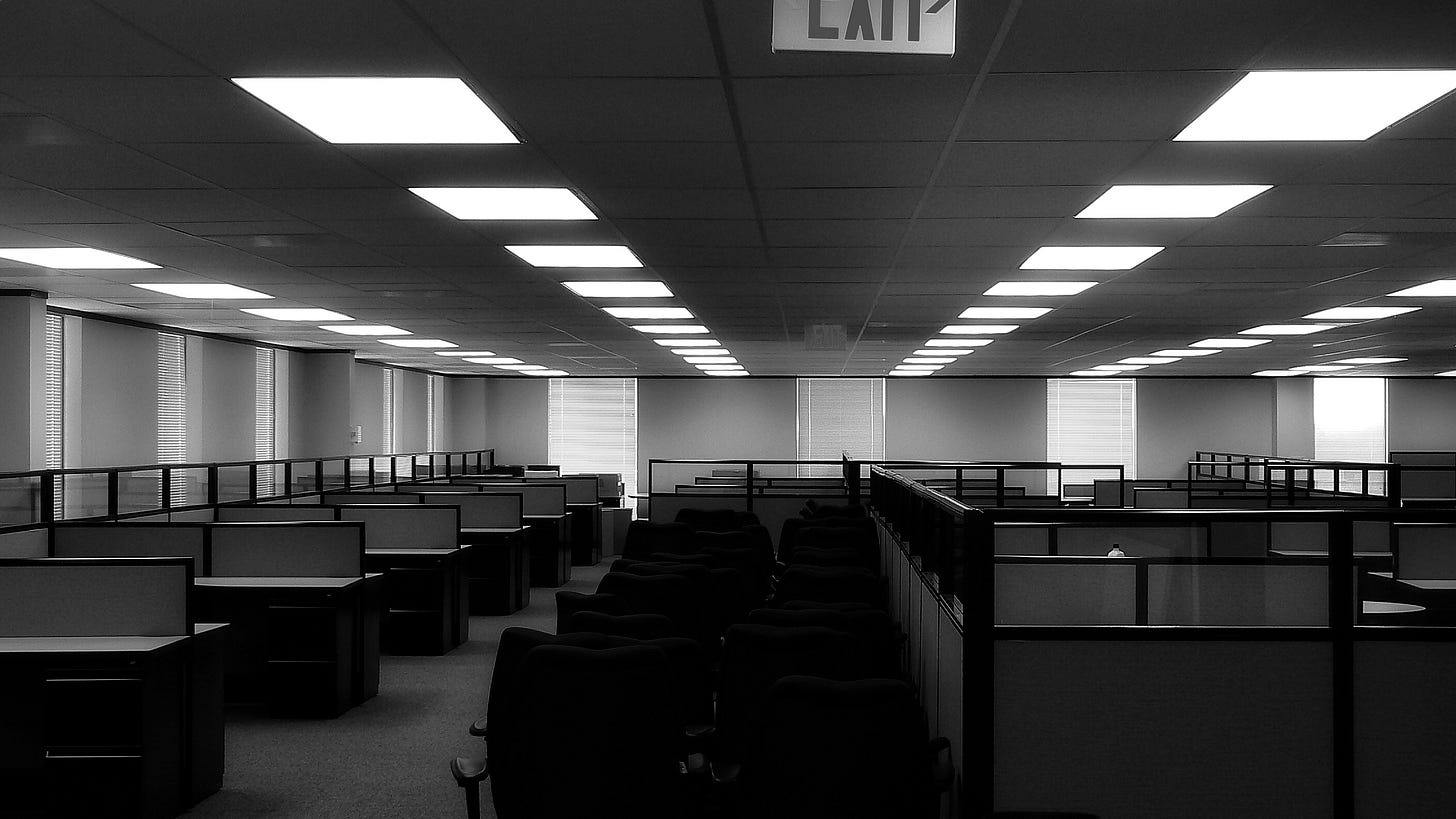

Still, though I have personally relished the transition to remote work, it was quite a shock to walk into the office. After leaving the reception area to walk down a long hallway, I was greeted with a sea of mostly empty cubicles. I estimate that in an open space of approximately 50 cubicles, there were only two or three people actually sitting there. Around a corner, I saw another sparsely populated array of cubicles. The glass-doored private offices lining the hallway were all empty.

Granted, I had arrived just before 1:00 p.m., so some people had gone out for lunch. When I emerged from a conference room about 60 minutes later, there were a few more people seated in cubicles, and a handful of others in the private offices. Nonetheless, at least this floor of this multi-floored office may have been no more than about ten percent populated. (There may well have been many more people on other floors, in the mail room, IT department and the like.)

I can attest that my former law firm is very much a going concern—a busy, thriving international law firm with more than 60 offices around the world. So a lack of people sitting together at desks in a midtown Manhattan skyscraper is not a sign of lack of success. On the contrary, the kind of law this firm practices is quite amenable to hybrid or remote work. There are infrequent face-to-face meetings with clients (who are spread around the country and around the world in any case), much of the day-to-day work consists of data entry done by paraprofessionals, and the firm is investing heavily in automation and Artificial Intelligence to take on many of the mundane tasks involved in a high-volume business involving the preparation and filing of visa applications. And the high-level work done by lawyers and corporate leaders—legal and policy analysis, strategic planning, finance, marketing and the like—is often best done solo after consultation with small groups of colleagues in any event.

What was absent when I walked into the office was the buzz, the energy, the vitality that used to permeate the place. If I were a young person entering the workforce today, I wouldn't even know what I was missing.

There is definitely something both gained and lost in pivoting to a mostly remote corporate culture. This is not a revelation, and I'm far from the first to opine on this subject. But here's my personal take-home message: what was absent when I walked into the office was the buzz, the energy, the vitality that used to permeate the place. For us old-timers, who already know everyone—and who know where to go or who to call if we have a question or need someone to help with a project—there is much to be said in favor of being able to work from home (or from anywhere). For me, I must admit it has restored (or created?) a work-life balance that I never actually had before in my professional career. In many ways, it has been positively joyful.

But if I were a recent college or law school graduate entering the workforce today, I wouldn't even know what I was missing. Much of the learning by new employees is best done by both formal and informal instruction or modeling from colleagues and mentors. When I was a young lawyer, I used to be able to walk out the door of my office and ask someone nearby a quick question about how to get something done. More important, I could walk down the hall and pop into the office of any number of world-renowned experts in the field of immigration law, and immediately get any guidance or mentoring I needed. Our firm always had an open-door policy, there were never any stupid questions, and there is simply no substitute for that kind of learning.

We also had a lot of fun! Even—or sometimes especially—in times of stressful deadline pressure, our partners and employees alike knew how to laugh, how to work hard together and then let off steam together afterwards. We had parties, oh so many parties … impromptu after-work get-togethers in the office or at nearby watering holes, private gatherings in partners' homes, or lavish holiday affairs in grand hotel ballrooms.

There is no question that the paradigm of white-collar workers commuting to an office every day to do work they could do from a laptop in their backyard has been permanently disrupted. The adaptive re-use of office space is inevitable, necessary and unstoppable.

This liminal moment in time feels eerily like a science fiction story in which environmental conditions have caused humans to banish themselves to solitary, sterile, temperature-controlled interior spaces, where we interact with other humans solely over computer screens.

Recent examples of extreme weather also come into play. We had torrential rain in the New York City area last week. If I'd had any urgent in-person meetings scheduled on Friday, I would not have been able to get there safely, if at all. Earlier this year, record-breaking high temperatures, and unhealthy levels of smoke from distant forest fires, similarly made leaving the house to get to an office untenable (or at least inadvisable).

But this liminal moment in time feels eerily like a science fiction story in which environmental conditions have caused humans to banish themselves to solitary, sterile, temperature-controlled interior spaces, where we interact with other humans solely over computer screens.

Imagine a world where shopping is done online with goods delivered to our doors (and let's acknowledge that, at least for now, this is possible only because of what we learned during the COVID-19 pandemic are the true "essential workers" who have no choice but to leave their homes to work). Cooking consists of putting pre-portioned, nutritionally-balanced meals into a microwave for five minutes. Meetings with lawyers or accountants can take place over Zoom. Many doctor's appointments take place online. Even certain kinds of sexual encounters happen on the internet, replacing the basic human need for physical intimacy with virtual rendezvous.

Oh, wait. Even though we have emerged from our homes after the height of the pandemic, we already live in that world. What's left? Are we all destined to become Japanese-style hikikomoris, recluses who live our entire lives at home?

Thankfully, I don't think we're there yet. But there is a real danger that, at least in the so-called advanced economies of the world, we are gradually sliding in that direction.

I'm reminded of Sheryl Sandburg, who not only famously advised women seeking leadership roles in the workplace to "lean in" but also admonished women struggling to find a palatable work-life balance not to "leave before you leave." We absolutely need to be planning for the long-term impacts on the economy of climate change, future pandemics, migration, political instability and the like. And re-thinking the way we work—reaping one of the few positive side effects of the pandemic—is an integral part of that.

I will personally never go back to work in an office again. But let's not leave the real world for a full-time virtual reality unless and before we have to.